7th of December 2024 | 6 min read

What we can learn from a successful self-taught artist

Time To Admit We Run in Circles

The contemporary art world prides itself on motion. New work appears constantly, trends cycle faster than they can be named, and visibility has become a kind of moral currency. To be seen is to exist; to disappear from the feed is to risk irrelevance. For many artists, this perpetual movement feels less like freedom than obligation. They are producing not because something insists on being made, but because stopping feels dangerous.

This environment rewards responsiveness over reflection. Artists are encouraged to keep up—to reference the right conversations, adopt the right aesthetics, signal fluency in whatever is momentarily dominant. The result is a strange contradiction: a culture that celebrates originality while quietly enforcing sameness. Everyone is urged to stand out, but only within a narrow band of what is currently legible.

Formal education is often framed as protection against this chaos. A degree, especially from a prestigious institution, is supposed to confer legitimacy, structure, and long-term security. Yet the numbers tell a different story. The overwhelming majority of graduates from top creative programs leave the field within a few years. Many end up in adjacent or entirely unrelated professions, carrying with them technical proficiency but little sense of direction.

This is not because they lack skill. On the contrary, they are often highly competent producers. They know how to render, compose, edit, fabricate. What they struggle to articulate is why any of it matters—why this work should exist, and why anyone else should care. They have mastered the mechanics of creation without being asked to interrogate its purpose.

Art schools, it should be said, are not villains in this story. They operate within constraints that are rarely acknowledged. Teaching technique is measurable; teaching meaning is not. Asking students to confront their motivations, values, and contradictions takes time, patience, and a tolerance for ambiguity that does not fit neatly into semesters or grading rubrics. If institutions centered the “why” rather than the “what,” fewer students would graduate. Fewer graduates would mean less funding. The system is not designed for existential inquiry.

So subjectivity becomes a convenient refuge. “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder” is offered as a kind of philosophical release valve. If everything is subjective, then nothing has to be defended too rigorously. Purpose becomes optional. Discomfort is avoided.

Outside the classroom, however, subjectivity offers little shelter. In the world artists eventually enter, response matters. Silence matters. Work that neither addresses a problem nor challenges perception tends to blur into the background. Many graduates encounter this reality abruptly. In school, the professor’s opinion was decisive. Beyond it, there is no captive audience.

The consequences are visible everywhere. Creative burnout has become endemic. Depression and creative paralysis are discussed openly, yet rarely traced back to structural causes. Artists are told to produce more, market better, stay relevant. Very few are encouraged to pause and ask whether the work itself is oriented toward anything meaningful.

This is what it means to run in circles: motion without movement. Output without direction. A system that prioritizes visibility over substance inevitably exhausts the people within it.

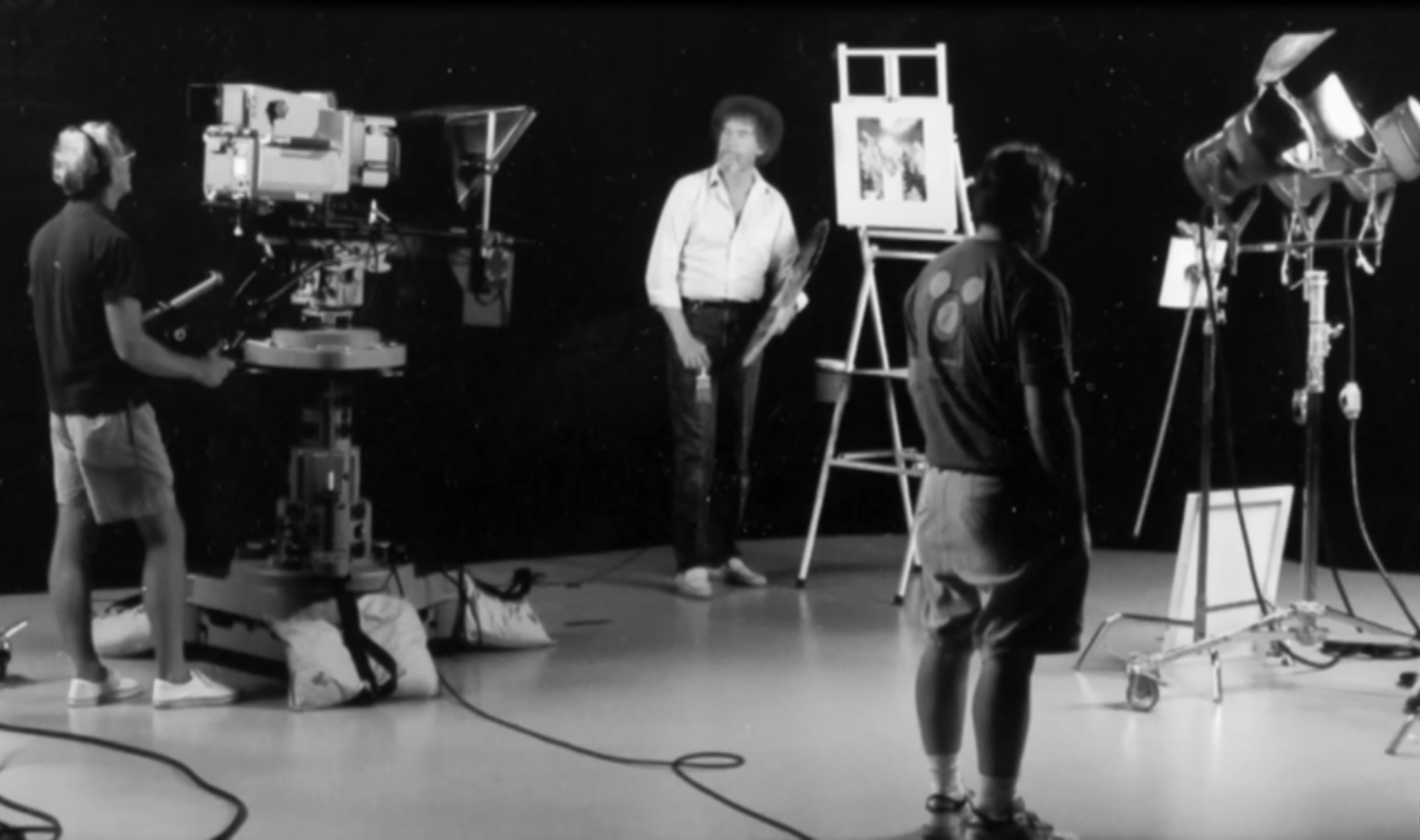

There have always been artists who refused this path. Some did so deliberately, others by circumstance. Maurizio Cattelan, who turned institutional critique into spectacle. Banksy, who bypassed the gallery system entirely. And then there is Bob Ross—a figure so culturally ubiquitous that he is often dismissed as benign nostalgia rather than taken seriously as a case study.

Ross had no formal training. He worked in a style many critics would label kitsch. And yet he reached tens of millions of people, offering something that more “serious” art often failed to provide: a sense of calm, permission, and purpose. His success is not something to imitate mechanically. But it is worth asking why it happened at all. The answer has less to do with talent or timing than with clarity of intent. Ross knew why he was painting. And that knowledge shaped everything that followed.

Recover Before You Get Up

Bob Ross did not begin as a gentle presence. Before the soft voice and pastoral landscapes, there was the United States Air Force. Ross spent two decades in the military, much of it stationed in Alaska, working as a medical records technician. It was a rigid environment, defined by hierarchy and control. He later described himself during this period as angry, hardened, and constantly yelling—a version of himself that felt increasingly alien.

The military gave Ross stability, but it took something in return. Years of suppressing emotion and enforcing authority left him hollowed out. By the time he left, he was deeply aware that something fundamental had been lost. What he needed was not advancement or recognition, but restoration.

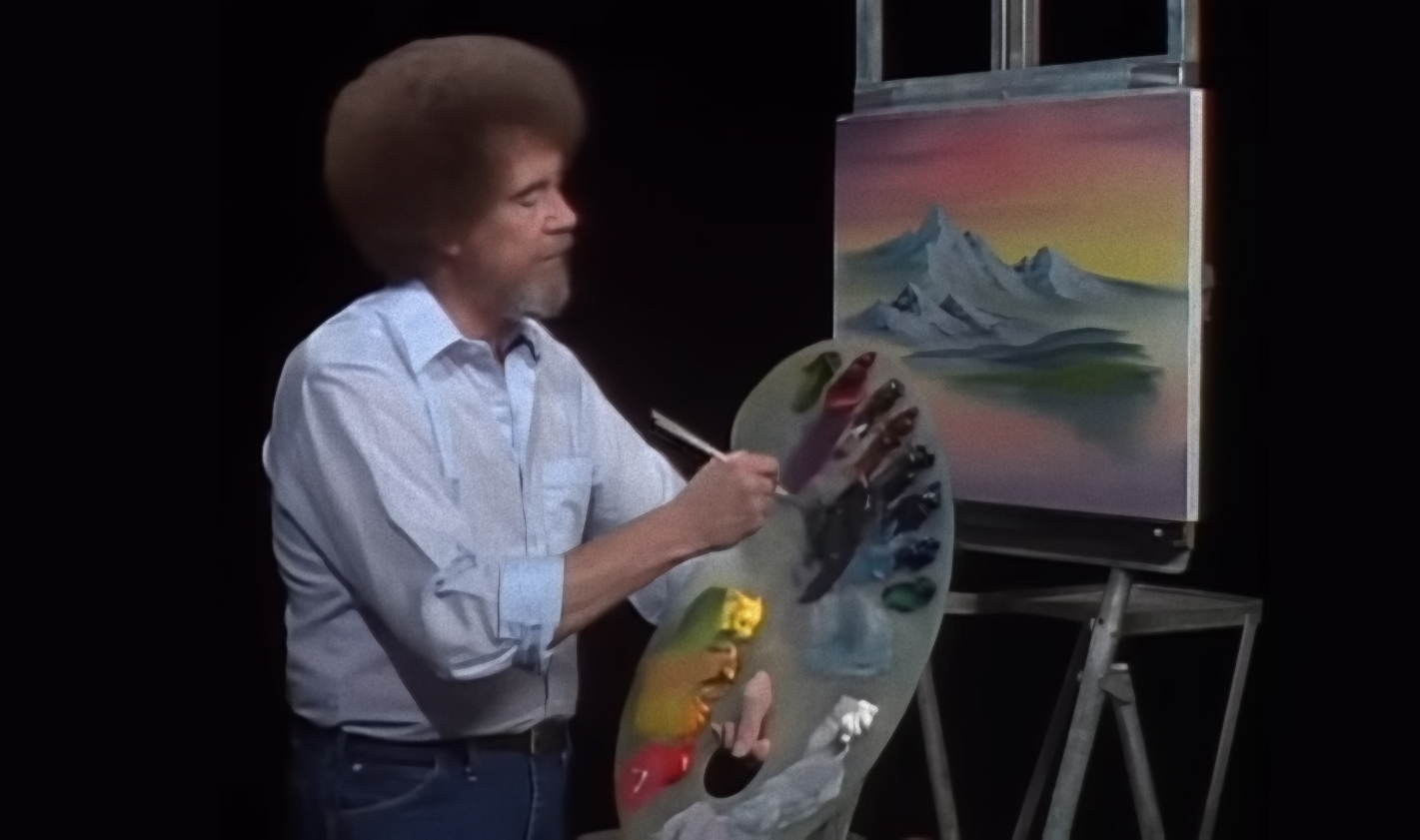

Painting entered his life almost accidentally. While stationed in Alaska, Ross encountered Bill Alexander, a German-born painter who popularized the wet-on-wet, or alla prima, technique. The method was immediate and forgiving: paint applied directly to wet paint, allowing landscapes to emerge quickly. For Ross, this was a revelation. The speed was not just technical—it was emotional. It allowed expression without prolonged self-scrutiny.

Art, for Ross, was not initially about ambition. It was survival. Painting became a way to access a part of himself that had been buried under years of discipline and constraint. When he retired from the military and began teaching art, it was less a career pivot than an act of self-preservation.

The early years were unremarkable by most standards. Ross was unknown. His classes struggled to attract students. He tried demonstrations in shopping malls, paid for expensive television advertisements, and traveled constantly. Progress was incremental at best. What sustained him was not external validation but the quiet certainty that painting was doing something necessary—for him and, potentially, for others.

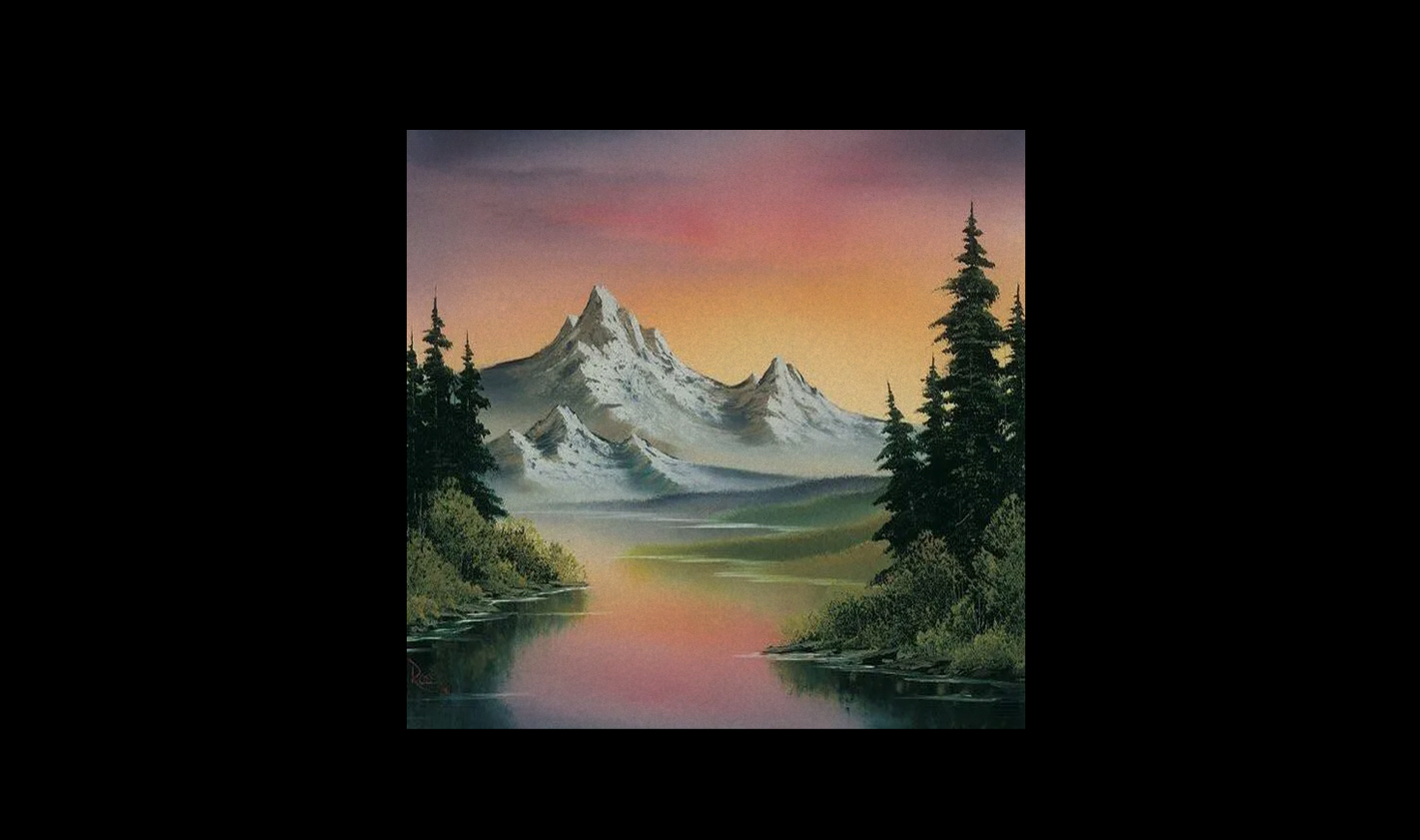

Crucially, Ross chose accessibility. He did not pursue technical virtuosity or conceptual obscurity. He leaned into imagery that was familiar, even sentimental. This was not a lack of sophistication but a strategic generosity. His work said, implicitly: you are allowed to be here.

Ross demonstrated something that many artists resist: you do not need to be healed to create. Creation itself can be the beginning of healing. But healing, he understood, was not passive. It required repetition, discipline, and showing up even when inspiration was absent.

For many viewers, The Joy of Painting functioned as more than entertainment. The show offered a rhythm of calm in otherwise turbulent lives. The language Ross used—“happy little trees,” “there are no mistakes, only happy accidents”—was not accidental. It countered a culture of judgment with one of permission.

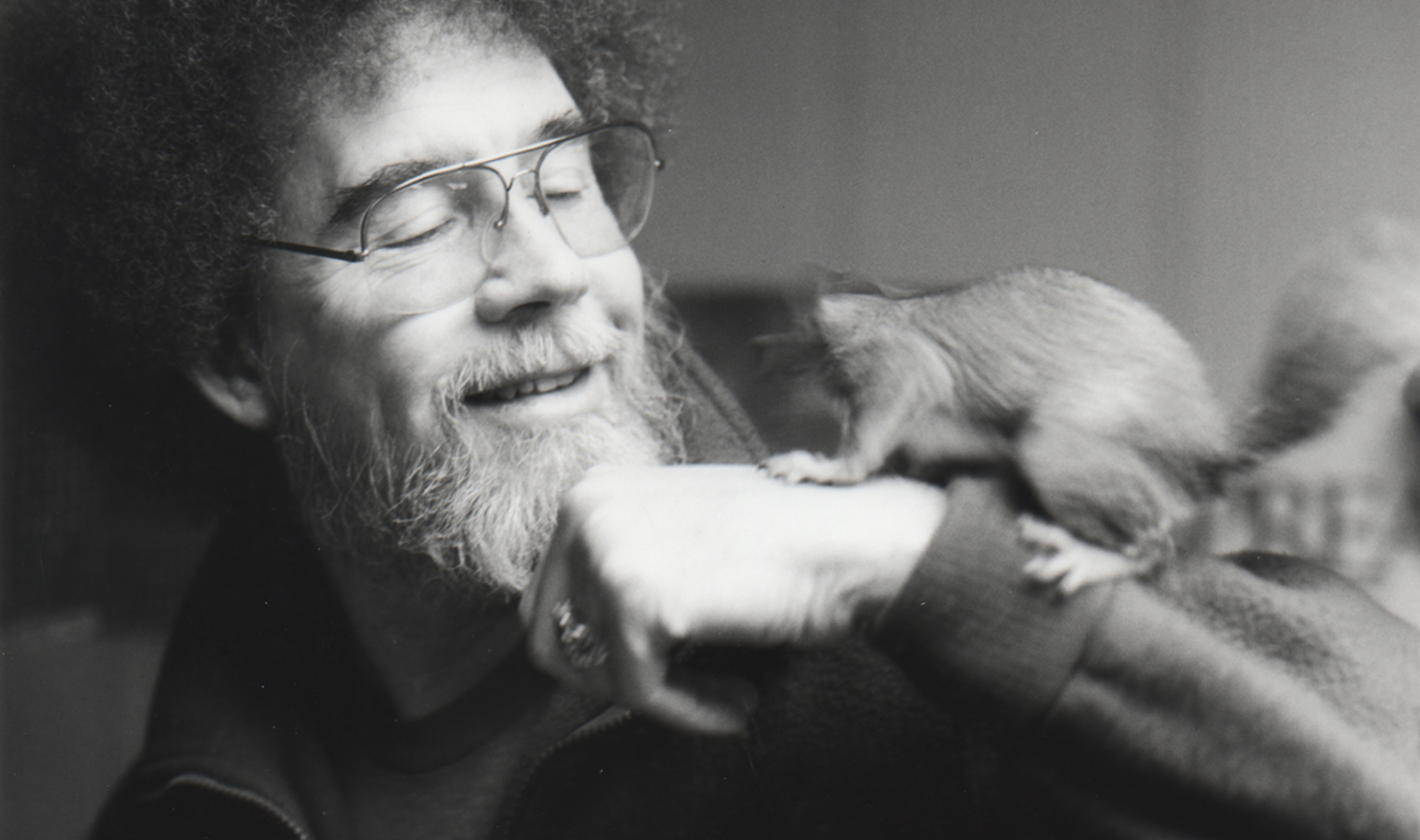

And yet Ross did not remain in this space indefinitely. This is where his story becomes instructive. Once art had helped him recover, he did not make recovery his identity. He did not build a persona around trauma. Instead, he allowed his work to evolve outward.

Teaching became central. The focus shifted from his own restoration to the possibility of helping others find theirs. Ross understood that survival is not the destination. It is the threshold. Too many creatives remain suspended at this stage, waiting for recognition of their pain. Ross moved forward. His past informed his work, but it did not confine it.

Stop Acting Like You Know It All

Before direction comes wandering. This is not a romantic notion but a neurological one. Neuroscientists refer to the Default Mode Network—the brain state activated when attention is not externally focused. It is during these periods of apparent idleness that disparate ideas connect, memories surface, and meaning begins to coalesce.

This state cannot be forced. It resists productivity metrics. Hustle culture has little patience for it. And yet, without it, creative work becomes reactive—shaped entirely by external inputs and expectations.

Ross cultivated this space deliberately. He spent long periods in nature, walking, observing animals, letting his thoughts drift. This was not escapism but preparation. For others, the equivalent might be music, long walks, repetitive manual work, or moments of solitude carved out of otherwise crowded lives. The activity matters less than the permission to stop striving.

Reflection alone, however, is insufficient. Ideas must eventually be shaped. Invention requires selection—the willingness to let most thoughts go in order to nurture one. Ross understood this deeply. Each painting that appeared effortless on television was preceded by dozens of preparatory versions. This rehearsal allowed him to be present, to respond fluidly to accidents rather than be derailed by them.

Ease, in this context, was not natural talent. It was the visible residue of invisible labor.

The final demand is commitment. Once an idea has revealed itself, it requires loyalty. This is where many creatives falter. Without a clear sense of purpose, every new idea feels equally compelling. Projects are started enthusiastically and abandoned quietly. What looks like exploration is often avoidance.

Conviction does not mean certainty. It means staying with a question long enough for it to deepen. Ross showed up repeatedly, not because every painting was inspired, but because the act itself was aligned with something larger than mood or outcome.

You cannot create only for applause. Applause is intermittent and unreliable. You have to know what compels you when no one is watching.

Nothing Worth Having Comes Easy

Many creatives exist almost entirely in execution. They are busy, productive, and perpetually behind. The system encourages this state, equating freedom with the ability to make endlessly. But without direction, this freedom collapses into chaos. Output becomes noise.

The prevailing message is simple: produce more. Market better. Stay visible. Rarely does anyone ask whether the work is oriented toward anything meaningful. This absence of inquiry is not neutral. It extracts energy without offering coherence in return.

Bob Ross’s work endures because it was relational. He did not paint only for himself. He painted for people who believed creativity was inaccessible to them. His work extended an invitation, not a challenge. It created connection rather than hierarchy.

This is what much contemporary creative culture lacks. Connection requires vulnerability and clarity. It requires acknowledging that art is not merely self-expression but communication. Work that speaks only inward rarely travels far.

There is one final discipline Ross practiced that is often overlooked: acknowledgment. He celebrated completion. Each painting ended with a sense of closure, not urgency. In a culture that values constant production, pausing to reflect can feel indulgent. It is not. It is how meaning consolidates.

Without reflection, work becomes transactional. Content is delivered, value is extracted, and the cycle resumes. With reflection, the process becomes formative. The artist changes alongside the work.

Nothing worth having comes easily—not clarity, not purpose, not connection. These are earned slowly, through attention, patience, and the willingness to resist the noise. Bob Ross did not escape the system by accident. He stepped outside it by understanding why he was creating in the first place.

And that, perhaps, is the lesson that remains most urgent today.